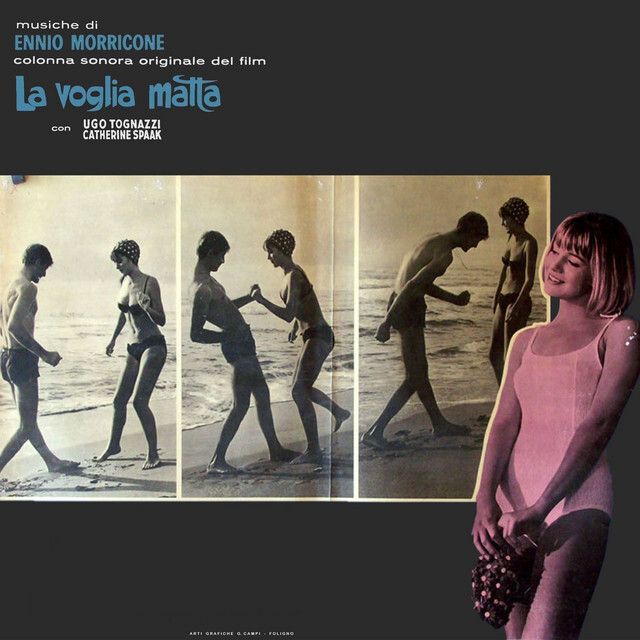

September’s Add of the Month: Ennio Morricone’s “La Voglia Matta”

Words by: Marion Suchowiecky.

As the music department’s resident “old-head,” Marion Suchowiecky reimagines the Add Of The Month series, writing about older records that deserve to live another day in the sun. Here, Marion highlights new, retroactive additions to the library and records that were added to the library some time ago but continue to be relevant, influential, or simply good. This month, Marion sits down to compose a letter to the KCSB community concerning Ennio Morricone’s scoring of “La Voglia Matta.”

It is the summer of 1962, and somewhere on the coast of Italy, a conservative businessman is driving his sports car along the highway when it suddenly breaks down. There, he meets a group of rowdy youngsters- Beats- and is smitten by one in particular- Francesca (portrayed by Catherine Spaak). What follows is a tale of summer, of unrequited love, a story of the allure of youth and heat and sand. Luciano Salce’s “La Voglia Matta,” or “Crazy Desire,” is a film set in the beautiful Italian Riviera, conceived in a different time and space. Yet, it is a film whose spirit is alive and well within the hearts of anybody who listens to its beautiful score.

What makes the stories of this particular region of the world, at this particular moment in time, so appealing? They are stories of a culture in flux, depicting the tug of war between the old and the new. They reimagine age-old narratives, setting them within a modern context, allowing characters to exhibit a realism that had never before been seen. All the while, these films maintain a particular level of fantasy, perhaps because they are set in unbelievably gorgeous settings and inhabited by undeniably attractive characters accompanied by the sweet sounds of Italian film music. The amalgamation of these factors play a part in the overall enchantment of Italian cinema in the early 1960s; I would venture to say that this elusive magic is masterfully conveyed in Ennio Morricone’s scoring of “La voglia matta.”

Scores, in principle, are a tool of the filmmaker with which they can highlight and heighten emotion in key scenes of a film. However, in the hands of a master such as Ennio Morricone, scores become standalone pieces of art, completely separate from the film birthing their existence. Morricone, is most famous for his revolutionary scoring of the Dollars trilogy, which features legendary films such as “A Fistful of Dollars,” “A Few Dollars More,” and “The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly.” These soundtracks used a low-budget arrangement of electric guitars drenched in reverb, bells, flutes, and rhythms that mimicked the trotting of horses (great video about those scores here). However, “La Vogglia Matta,” was not a spaghetti western, but a classic commedia all’italiana, verging on neo-realism, and Morricone approached it as such.

Listening to a score in one sitting, as I personally love to do with any new record, is a unique and informative experience. This is because a score compiles all of the moments of heightened tension, scattered throughout the film and buffered by more or less neutral scenes, into one cohesive, condensed work. Thus, a well-made score not only tells the story of the film for which it is constructed but furthermore touches upon universal truths and emotions, providing the listener with entirely new information that only the open-ended nature of music can provide.

The score of “La Voglia Matta” features a melding of genres. In the first track, “Agosto Jazz,” the listener is transported to a distant world, where a traditional, piano-drum-bass-guitar rhythm section plays ii-V-i chord progressions, backing the big brass band and supporting soloists in their carefully improvised endeavors. The next track, “Carporal Twist,” could be described as the rowdy, rebellious daughter of “Agosto Jazz.” As one might guess, “Carporal Twist” features twist, a dancing music genre for teenagers in the late 50s and early 60s. This song comprises brass and the traditional rhythm section but is quicker and more playful, adding surf rock-esque guitars and rock n’ roll rhythms into the mix. Within these first two tracks, the listener can feel the tug of war between the old and new, the theme which will be explored throughout the rest of the film and its accompanying score. Antonio, our businessman, represents the old and the young Francesca- a vision of freedom, a woman who will unflinchingly stand in the middle of the road in the face of a fast-approaching Alfa Romeo- representing the new.

The next track, “Nuvole,” features Italian singer Jimmy Fontana. The word “nuvole” refers to someone with their head in the clouds. It’s a laid-back, stripped-down, Latin-jazz-influenced track—Fontana scats over a groovy electric guitar and bongo drums. One can imagine our protagonist beginning to let loose, matching the wits and attitude of Francesca. As Antonio lets go of his conventional thinking, he becomes enamored with Francesca and everything she represents. This is conveyed throughout the following two tracks, clearly influenced by the more classically inclined Italian film score composer, Piero Piccioni.

In “Sole e sogni,” a sporadic harp accompanies a sweet string section, but what stands out most is the beautiful siren-like vocals, potentially representing Francesca’s allure. In “Desiderio di te,” which translates to “longing for you” in English, the wide variety of string instruments, set to a swinging jazz rhythm, allow one to perfectly picture the almost cartoonish image of a fool drifting in love. This image is further developed in “Francesca,” a playful track that abandons the classical feel of the previous two tracks, opposingly featuring snappy guitar playing with a Caribbean sense, bongos, and what sounds like a train whistle.

The next track, “Un povero matusa,” is very brief. But it is remarkable for the way it conveys feelings of utter uncertainty and vulnerability in the first half and proceeds to completely change in the second half, conveying a significantly less ambiguous feel. This track once again features strings and even a flute. However, in the second half, the harp replaces the flute’s prominence as it plays the lead melody and makes the song return to the innocent, fool-in-love sound.

In “Miraggio Africano” and “I nuovi Giovani,” vulnerability and uncertainty are further explored. Ennio Morricone’s Spaghetti Western style shines through in these tracks. In “Miraggio Africano,” the drums resemble many of the tracks in the soundtracks of the Dollars Trilogy, and they feature innovative synthesizer-like sounds. If it weren’t for the continued prominence of flutes and a string section within these two tracks, they could almost be transplanted into a Mexican stand-off scene in a Western. Finally, the last three tracks represent the character of Antonio’s realization that despite his deep, unrequited desire for Francesca, he will ultimately never fit into her world. Here, we picture him as he resigns himself to the constricted bourgeois life he had previously created for himself and is therefore doomed to live out.

The soundtrack, as a whole, feels like a final breath of fleeting warmth. The last three songs specifically remind one of the last days of summer. Those days when one looks back at all the missed possibilities and weighs them against the brief moments of splendor under the sun, realizing simultaneously that any backtracking is illusory. Yet, each year, one reaches and anxiously waits for the optimism derived from our time in the sultry summer weather. Like Antonio, we foolishly hope and long for a taste of the freedom that Francesca’s character so beautifully embodies and Morricone’s score masterfully captures.