Board of Supervisors Balance of Power at Stake in Redistricting

Board of Supervisors Balance of Power at Stake in Redistricting

New independent commission is beset by partisan wrangling

By Melinda Burns

Santa Barbara County’s first-ever independent redistricting commission has begun its work with the kind of partisan conflict and maneuvering that the voters had hoped to avoid when they approved the new system in 2018.

The stakes are high, tempers are hot and rhetoric is rampant as the County of Santa Barbara Citizens Independent Redistricting Commission embarks on the difficult task of redrawing the boundaries of the county’s five supervisorial districts, based on 2020 Census data.

The supervisors ostensibly are non-partisan; as a political matter, however, the outcome of the redistricting will determine which party and which fundamental values – liberal or conservative – control the powerful county Board of Supervisors and the $1 billion budget that it oversees.

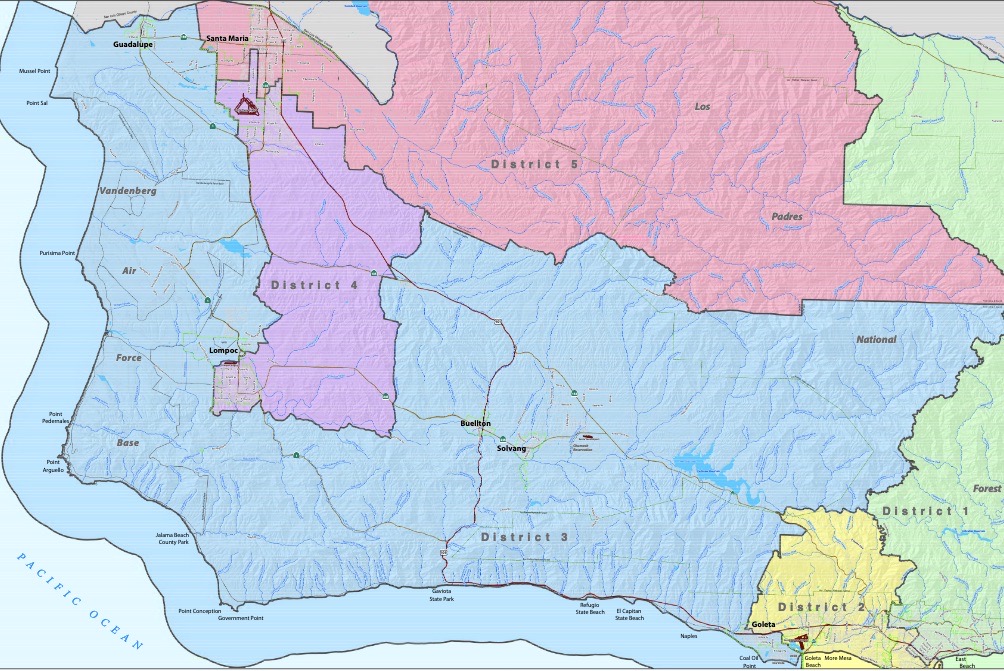

The key question: The fate of the third supervisorial district, the largest in the county, is in play. It includes both Isla Vista, a monolithic Democratic enclave of 27,000 people, mostly students, living on the coast next to UCSB; and the agricultural Santa Ynez Valley, a more conservative community on the other side of the Santa Ynez Mountains.

This is the swing district that for 30 years has given Democrats a 3-2 majority on the board, along with Santa Barbara and Goleta. In the past, redistricting was done by the board itself, every 10 years. Now, the North County population, estimated at 234,000 in 2019, has surpassed that of the South Coast, at 210,000; and the Republican Party sees its chance to seize the upper hand.

Political diversity

Republicans make up only 25 percent of registered voters in the county, but their representation on the new 11-member commission has been a major topic of discussion since the group began forming itself last October.

In December, the county Republican Party and the California Hispanic Chambers of Commerce sent a joint letter threatening to sue the commission unless it added two Latinos, for a total of four; and one or two Republicans, for a total of up to three, to reflect the ethnic and political diversity of the county.

“I worked on the campaign to get this measure passed,” Bobbi McGinnis, who signed the letter as the Republican Party chairwoman, told the commission on Monday night. “I would like to see it followed to the letter of the law.”

And the commissioners complied, unanimously naming a third Republican to join their ranks. Cheryl Trosky of Montecito, a retired nurse and the former owner of a home health care service, is the group’s 11th member. She replaces Lollie Katz, a nurse practitioner and Carpinteria resident who quit her post in protest on Feb. 2, saying she lacked “the endurance or strength of belief to continue.”

“I didn’t have the stomach for it,” Katz said this week. “I felt we were being pushed beyond what was reasonable by the Republican Party. I had no idea how political this was going to be.”

Katz had been chosen by lottery last fall as one of the first five commissioners from a pool of 45 applicants provided by the County Registrar of Voters. Early on, she said, someone filed a public records request with the county to obtain her iPhone records, alleging that she may have been texting about public business during a meeting. Katz said she had not been texting, period, and the complaint was withdrawn; but it left her feeling as if she had been targeted.

“I think I was identified from the very beginning as being a lifelong Democrat,” Katz said. “I represent that with a lot of pride, frankly.”

Tough question

Trosky fielded one pointed question on Monday: it was from Commissioner Megan Turley, a Democrat who, referencing a previous public comment, asked her to explain a letter she had written to the Santa Barbara Independent last spring, in which Trosky had asked, “Isn’t it time for us to allow to gather for graduations, concerts, weddings and other community events if we can gather to protest and honor George Floyd and Black Lives Matter?”

Noting that the county Public Health Department has declared racism and police brutality to be a public health crisis, Turley said, “I just think it’s important specifically to our communities of color in Santa Barbara that they understand that she is going to be able to serve them in the same way that she’s able to serve other constituents.”

Trosky responded that her words last spring, which she didn’t recall, “in no way” should reflect on her future service with the commission.

“My son didn’t get to experience his graduation and a lot of things were going on and it was a pretty emotional time for a lot of people,” she said. “I certainly have deep compassion for what happened to George Floyd … I have made a commitment to helping people that are disadvantaged and less fortunate.”

Commission makeup

The county commission is one of only two voter-created redistricting commissions in California: the other is in San Bernardino County. Under rules approved by Santa Barbara County voters in 2018, the makeup of the commission is supposed to reflect the ethnic, geographic and age diversity of the county and be “as proportional as possible” to the percentages of voters registered with each party, though not by applying “formulas or specific ratios.”

Since last October, Glenn Morris, a Republican who is president and CEO of the Santa Maria Valley Chamber of Commerce, has served as chairman, winning praise from all sides. Besides Katz, another Democrat resigned this winter; he voluntarily gave up his seat to a Republican in January.

With Trosky’s appointment this week, the commission is now composed of four Democrats (36 percent of the 11 members); four (another 36 percent) who stated “no party preference;” and three Republicans (27 percent).

That means that Democrats are underrepresented on the commission: 46 percent of registered voters in the county are Democrats, 28 percent are unaffiliated, and 25 percent are Republicans.

Latinos are underrepresented, too. The commission now includes one Latino and two Latinas; they represent 27 percent of the 11 members. Nearly 40 percent of the county’s population is Latino.

The law firm

In another contentious sticking point, Republican leaders have opposed the commissioners’ choice of Strumwasser & Woocher LLP, a Los Angeles public-interest law firm, to represent them. They contend that Fred Woocher represented former Third District Supervisor Doreen Farr in a court case within the last eight years, in violation of the commission’s conflict of interest rules.

In a letter to the commission this month, Woocher said there was no such violation because Farr won her case in 2010. Woocher said he was awarded attorneys’ fees in 2011, though it wasn’t until 2013 that Farr’s former opponent, who filed the lawsuit, exhausted his appeals.

The county supervisors will take up the question of the commision’s law firm at a hearing on March 9.

“Predictably, the independence of the commission is under siege by progressive activists,” Andy Caldwell, executive director of the Coalition for Labor, Agriculture and Labor, a conservative advocacy group, wrote in the Santa Ynez Valley News last week. He noted that COLAB sued the county 20 years ago over redistricting “because of the Isla Vista machination.” It was Woocher, Caldwell said, who successfully defended the county against that lawsuit.

“The progressives are counting on Woocher to work his magic again,” he wrote.

On Monday night, Caldwell told the commissioners, “You guys are being influenced vis-à-vis subterfuge and innuendo by people claiming they’re watching out for your independence, but I beg to differ.” Among others, he named Spencer Brandt, organizing director of the Democratic Party, president of the Isla Vista Community Services District board, and, like Caldwell, a frequent speaker at commission meetings.

“It’s called public comment,” Brandt said on Tuesday – “and Mr. Caldwell knows that, because he’s made his career providing public comment. What I see going on is that the Republican Party made a really concerted effort to sue the commission so that they could get their way.

“I am a 24-year-old living in a rental apartment in Isla Vista. I will not be filing any lawsuits or threatening anybody, anytime soon. I’m engaged in the process because I want the commission to succeed.”

In the coming months, the commission will begin inviting residents to submit their own district maps, based on American Community Survey data from 2015 to 2019 provided by the U.S. Census Bureau.

Because of the pandemic, the Bureau is not expected to release total county population numbers for 2020 until Sept. 30, six months later than originally planned. The state may not release prison population numbers until Oct. 30. That would leave only six weeks for the county’s independent commission to draw up its final maps; the state deadline for redistricting is Dec. 15.

Melinda Burns volunteers as a freelance journalist in Santa Barbara as a community service; she offers her news reports to multiple local publications, at the same time, for free.