Judge Quashes UCPD Search Warrant for Pro-Palestine Instagram Accounts

Photo credit: KCSB News file photo

Story by Ray Briare || Listen to the story on SoundCloud

—

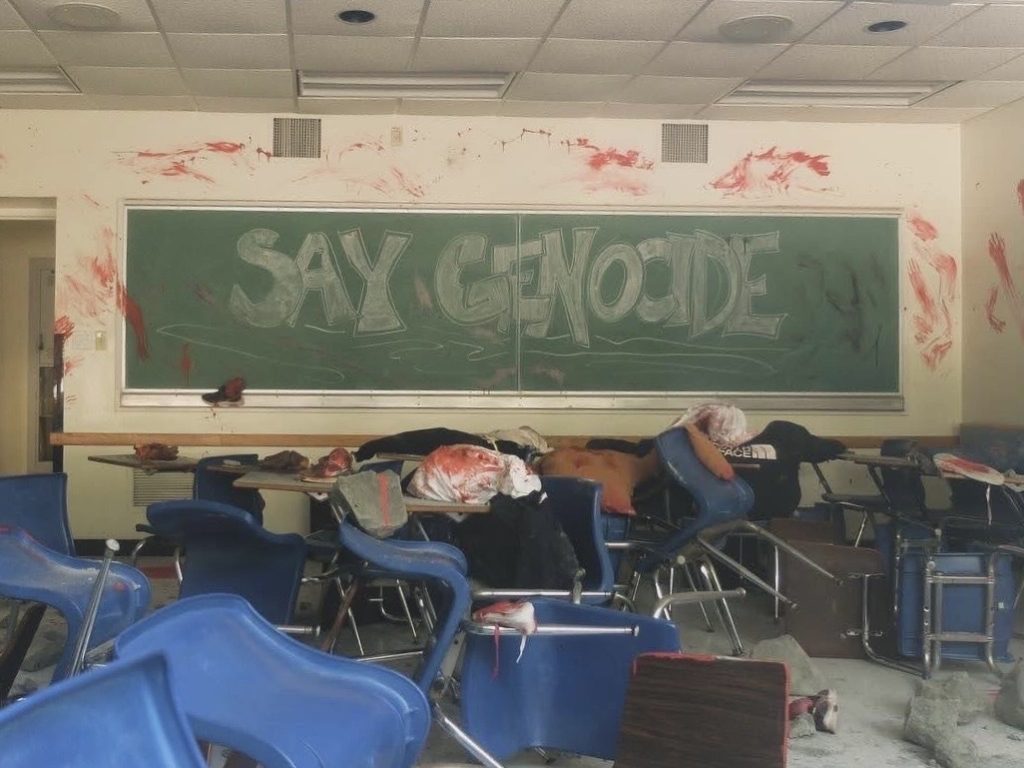

On June 10, 2024, anti-war protesters occupied Girvetz Hall on the UCSB campus. They transformed a classroom into a scene of a study hall bombed in war, with overturned desks, bloodied bodies, rocks and rubble. On the roof they raised two flags: the Palestinian flag, and, upside-down, the American flag.

The same day, the Instagram account SayGenocideUCSB featured a post claiming responsibility for the occupation of Girvetz and issuing demands of the University, such as an official statement recognizing genocide in Palestine.

That night, around 11:30, counter-protesters arrived and tried to seize the American flag. A physical confrontation ensued, some of the occupiers suffered minor cuts and bruises, and the counter-protesters fled.

The next night, shortly after 1 in the morning, officers in full riot gear — UCSB PD and Santa Barbara Sheriffs — surrounded Girvetz, blocking all points of entry or exit. UCSB Police deployed a piece of military equipment called the LRAD, or Long Range Acoustic Device, an expensive and very powerful loudspeaker, or sound cannon, through which they issued orders to disperse.

Eventually, officers entered the building. But after a two-hour search, they didn’t find anybody. Police apprehended no one that night, and today, nearly seven months later, they have still arrested not one person.

What they have found are some supposed crimes. They claim that damage to classrooms, an HVAC unit, and a roof hatch was over $40,000 of vandalism. When the occupation began, some custodians hid themselves in a closet. Police equate this with kidnapping. Police also allege burglary and conspiracy, and they want to charge the occupiers with all four crimes.

But who are the occupiers? In a search warrant issued September 11, UCSB Police want Meta, the parent company of Instagram, to tell them who created the accounts SayGenocideUCSB and UCSBLiberatedZone. They also want the IP addresses of anyone who ever posted, commented, liked, or even viewed the pages.

Rather than comply immediately, Meta notified the creators about the existence and scope of the search warrant. Soon some John or Jane Doe hired Santa Barbara criminal defense attorney Addison Steele to quash the warrant.

In a Santa Barbara Superior Court hearing on November 22, while attempting to show the warrant lacked probable cause, Mr. Steele presented the legal definitions of kidnapping, burglary, and conspiracy, and maintained that the allegations do not meet the crimes’ criteria. He also argued that there is no evidence connecting all the alleged vandalism to the occupiers, and certainly not to the Instagram account creators. Furthermore, Mr. Steele contended that the University Police seeking information about anyone who had ever interacted with the Instagram accounts is overly broad, a violation of privacy, and would chill protected free speech.

Jonathan Miller, the attorney hired by the University, countered that the police need the entire haystack to find the needle.

Judge Pauline Maxwell heard the arguments as well as amicus comments from Jacob Snow of the American Civil Liberties Union. She set December 20 as the day she would render a decision, and encouraged the two parties to negotiate some agreement before then.

That didn’t happen, so the attorneys showed up ready to battle again. But Judge Maxwell wasn’t having it.

MAXWELL: The issue here is that when First Amendment and privacy rights are implicated, the state has to show a compelling interest that justifies invading those rights. I do believe that the identity of anyone who posted anything about the events at Girvetz Hall, there is such a compelling interest in the identity of those people. I don’t believe there’s a compelling interest in an unlimited number. There’s not even a date and time limitation on the warrant. It could expose an unlimited number of people’s privacy and First Amendment rights and I think that it’s overbroad. And so I want to make clear that I’m quashing it only on the basis that it’s overbroad and not on the basis that there is not some relevant material here that should be produced. …And I just don’t believe there is a compelling state interest in the identity of everyone who looked at these websites. I think it’s similar to the NAACP, not being required to disclose its membership list, in White versus Davis. I view the membership list as akin to everybody who joined this website or looked at it. And the court said that that was overbroad. So I’m going to go with that and I’m going to quash the warrant and obviously UCSB is free to seek another warrant that is not as broad.

So, will UCSB seek another warrant? We asked, and Kiki Reyes from Public Affairs and Communication gave us what she called “our official university statement”: QUOTE “The University of California has a long-standing commitment to academic freedom, free speech and expression, and the right to civil protest. The criminal investigation into the unlawful occupation of the Girvetz building is ongoing, and the University acknowledges the court’s most recent decision concerning the warrant’s breadth of scope.” END QUOTE

Does Addison Steele think the police will seek another warrant?

STEELE: I would be shocked if they didn’t.

And what did he think of the judge’s ruling?

STEELE: She had clearly done the research, read the cases, read everything and determined that the warrant lacked probable cause. That it was overly broad, which was what my whole argument was the whole time. That it captured too many people and that there wasn’t a nexus between the Instagram pages and whoever were their creators, whoever saw them, whoever posted on them, and the people that went into Girvetz Hall, and at least theoretically trespassed and damaged an HVAC unit. And I also argued in my papers that there really wasn’t even a nexus between the protesters and the damaged HVAC unit. So in the end she did say she did quash the warrant, but she did say in open court that she did think that there that the police could create a warrant that would meet probable cause. So I don’t know what that warrant is. I would hope to see it first, but I don’t know what kind of warrant can be created in this situation.

KCSB News Director Rosie Bultman spoke to ACLU attorney Jacob Snow about his amicus brief and the Judge’s ruling.

BULTMAN: To what extent do you think that the ACLU’s amicus brief about free speech impacted this decision based on what the judge said, as well as based on your own insights?

SNOW: Some of the arguments that we made in our amicus brief certainly seemed to resonate with the court. We talked about the importance of protecting speech in the university and higher education context, and we referenced the case called White versus Davis, which underscored how important those privacy interests are on campus. And we also referenced a case in our brief called NAACP versus Alabama, which established that there are strong privacy interests and free speech associational interests in the membership list associated with, in that case, the NAACP. …And it did seem like those points were the ones that resonated with the court. It was certainly good to see that the court was being so thoughtful about the privacy and free speech issues.

BULTMAN: Do you think that there’s anything particularly significant about this case in terms of its ruling around social media and free speech? Again, this has been going on for a few years now, but it is like a fairly new legal precedent. So do you think that this case is setting or reinforcing a legal precedent around digital privacy?

SNOW: Yeah, I think this is a case that kind of makes an application of the law to a new context. In my view, this is not a controversial application of the law. You know, those cases like NAACP versus Alabama and White v. Davis from the California Supreme Court really do apply clearly to the modern age where so much social and political activism is happening on campus and it’s happening on social media. And so it’s very good to see that that application is being made by courts and it was made in this case. And so that’s the importance of the case I think is that it’s a strong signal to law enforcement and to the government that social media activism and campus activism are really the same kind of vital free speech activities that have motivated such strong protections historically and those strong protections still exist today.

So, what’s next? Here’s Addison Steele again:

STEELE: Well what’s next is that the UCPD write up a different search warrant. I’m very confident that they will consult with the DA’s office and that they will try and write a tighter warrant being more focused on their probable cause. And probably try to find a nexus between the protesters and the damaged HVAC unit. Again, I don’t see how they’re going to do that but that would be their next step. …So if they, if Meta doesn’t notice, you know, all of a sudden these kids could be having the police knocking at their door and taking them to the station and interrogating them and you know, without ever having seen it coming. So I’m hoping that Meta will let us know if a new warrant is served on them.

And what does Jacob Snow think is next?

SNOW: I think it’s entirely possible that they will seek another warrant. And you know when they do so, I hope they take into account the really strong direction that the court offered in terms of keeping information about people’s social media activity out of the scope of that warrant.

With Rosie Bultman, for KCSB News, this is Ray Briare.