Of Ashley, Wolgamot, and the Languages of Art

words by Liam Hogan

Last summer, I became completely obsessed with two major works of art: SMiLE by The Beach Boys and the book-length poem “In Sara, Mencken, Christ and Beethoven There Were Men and Women” by John Barton Wolgamot. The latter is discussed pretty significantly less than the former, so I thought it might be worth covering on my KCSB program “Beat Generation,” which I did in October. However, it kept rattling around my head as fall crept into winter, accumulating mass as it went, and eventually this article was born. Read on to see why I think you should care about this bizarre and impenetrable work, and how it relates to the impact of journalism on independent art and the history (and potential future) of the avant-garde…

Dedicated to Keith Waldrop and Robert Ashley, without whom this article would not exist. And, of course, to John B. Wolgamot, poet, genius, and visionary.

Keith Waldrop first came upon the book “In Sara, Mencken, Christ and Beethoven There Were Men and Women” in a used book store in 1957. It initially stood out to him for its unusual proportions (four and three-quarter inches tall by seven and three-quarter inches wide,) but upon further inspection it also contained no identifying information other than the author’s name, John Barton Wolgamot, and the year of publication, 1944. Beyond the title page, which contained only the lengthy title and the name of the author, the book contained 128 pages of variations on the exact same sentence, an example of which can be seen below:

“In her very truly great manners of Gustave Flaubert very heroically Helen Brown Norden had very altruistically come amongst his very really grand men and women to Benjamin Jonson, Franz Werfel, Grazia Deledda, Jean Giono, Richard Dehmel and Christopher Marlowe very titanically.”

Flipping through the book, Waldrop discovered that the only variation between pages was the lists of names and certain adjectives. Immediately intrigued by the eccentric structure, he did some research on its author, but was able to find very little concrete information: only that he was alive, living in New York, and he had another book, this one entitled “In Sara Haardt There Were Men and Women.” Upon purchase from a vanity press in the East Village, Waldrop discovered that, besides the altered title and minor printing disparities, the books were identical (I have to imagine that this is the point at which the mystery of this discovery reached something nearing the point of obsession).

Roughly 10 years later, during his time as a graduate student at the University of Michigan, Waldrop shared this bizarre book with his peers, the most relevant of which was one Robert Ashley, at that time a speech researcher by day and experimental musician by night. Ashley was immediately entranced, and reportedly declared that “here was the book he had always wanted to write.” Ashley would later decide to fully commit himself to music, and eventually held the position of director of the Mills College Center for Contemporary Music. There, Ashley set out to create his “masterpiece,” which was to be based on the text of “In Sara, Mencken, Christ and Beethoven There Were Men and Women.” He wrote a letter to Waldrop asking for permission to use his copy of the book, which was granted.

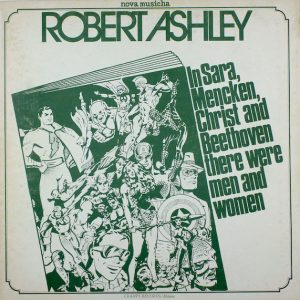

Released in 1972 by Cramps Records, Robert Ashley’s “In Sara, Mencken, Christ and Beethoven There Were Men and Women” attempts to adapt the text of John Barton Wolgamot’s book into what Ashley called a “television opera,” an idea that would go on to inform the rest of his musical career. The actual record itself is more of an outline for this “opera” (which was never developed), but it nonetheless exists as its own complete work. The piece is built upon Ashley’s observation that every page of the book could be read within the exhale of one single, slow breath, which I urge you to try for yourself. You will notice it forces a sort of metered, soft-spoken reading unusual in spoken word poetry. Ashley furthered this by editing out his inhalations between pages, giving the work a quality of one gargantuan, tumbling exhalation. Underneath the voice, Ashley (with help from his student Paul De Marinis) placed a layered bed of complex electronic sounds, the timing and placement of which was based on the names used in the source text. Beyond these basic descriptions, I am entirely unable to explain the way that these elements come together to create a tone entirely its own, a world unto itself which you are permitted to live in for barely 40 minutes. I urge you to listen to as much as you are able.

I think now is a good time to mention that in 2001, Lovely Music, Ltd. did an exhaustive remaster of Ashley’s “In Sara, Mencken, Christ and Beethoven There Were Men and Women,” and in the liner notes Keith Waldrop and Robert Ashley wrote a combined 35 pages on their love for this text — and their experience meeting its creator — which is the sole source for much of this story, and this article would be impossible without it.

After completion of his work, Ashley briefly toured it around places like Germany, Southern California, and New York. After the show in Southern California, a woman came to Ashley and asked if the piece was based on the book by John Barton Wolgamot. Ashley was taken aback — having previously thought this book was entirely unknown to everyone but himself, Waldrop, and a few other close friends — but confirmed that it was indeed. She said that she had been a close friend and confidant of Wolgamot’s during the creation of the book, and that she was sure he would love to meet Ashley after the New York show. Ashley agreed, but quickly realized that he had neglected to ask permission for use of the text from anyone but Keith Waldrop, and, in any case, was nervous about meeting this titanic and mysterious figure, so asked Waldrop to accompany him to their meeting.

They met Wolgamot in the lobby of the Little Carnegie Cinema, a small New York City theatre that he managed. According to Waldrop, Wolgamot seemed relatively uninterested in hearing the recorded piece itself, but he did presciently remark that it would have to be a “breathless” reading. He offhandedly mentioned that he’d been working on a sequel to the book, to which Waldrop cautiously inquired whether it would contain the same text as his first two books. Wolgamot replied “Oh, same text, same text,” but with an entirely new title page. According to both Ashley and Waldrop, Wolgamot seemed perfectly cogent and clear in his intentions. This was not a prank, performance art, or any sort of joke to him. Waldrop writes:

“In 1929, Wolgamot said, he heard for the first time Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony. He was bowled over. And as he listened, rapt, he heard, somehow, within the rhythms themselves, names—names that meant nothing to him, foreign names. It was these names, he realized, that created the rhythm, bearing the melody into existence.

He checked out from the library a large biography of Beethoven. And in that tome, he found, one after another, all the names he had heard ringing through the symphony.

And it dawned on him that, as rhythm is the basis of all things, names are the basis of rhythm.

Names determine character, settle destiny. ‘You can see that in the 15 great novels,’ he says. ‘Take Tolstoy. What does this remind you of: Annaka rennina annaka rennina?—it’s a train, of course. That’s why she’s killed by a train.’

‘That’s why,’ he said, ‘when a woman marries and gives up her name, she gives up her personality.’

Wolgamot decided—about 1930—to write a book.

He wrote one name to a page.

But he knew it could be richer. Names react to one another. He made long lists of names and held the list next to the pages of his projected book. When certain names came near each other, there was, he said, ‘a spark,’ and that was how he knew they went together. In this way, three names gathered on each page, and then around those three clustered multitudes of names.

And still something was lacking. Each page rhythmically complete, there was no impulse to go from one page to the next. There had to be a matrix, a sentence, to envelop the names. So far, he had spent a year or two composing his book. The sentence, a sentence to be repeated, more or less identically, on each page—this sentence took him ten years to write.

‘It’s harder than you think,’ he said, ‘to write a sentence that doesn’t say anything.’ ”

I can understand how someone could read the poem or listen to the spoken word in isolation, without a little bit of this context, and it could seem arbitrary, or repetitive, or even pretentious if they were being particularly uncharitable. But upon a deeper dive, you begin to see the obsession, precision, and overwhelming vision that Wolgamot had in the composition of this poem. For instance, he told Waldrop and Ashley that he was unsatisfied with two names among the 128 pages, “Camille Pissarro” and “Thespis,” because he was bothered by the first syllable of one and the second syllable of the other. He would later update Ashley that the problem had been solved, by substituting “Peter Cornelius” and “Ruth Rage” respectively. This level of detail and thought strikes me as unimaginable, and is proof of a logic underpinning this work that is beyond you or me. But in 1930, when he penned it, John Barton Wolgamot became a master of a completely novel system of writing that had no predecessor and, essentially, no successor. It was relegated to used bookstores and consigned to obscurity.

After their meeting in the Little Carnegie Cinema, Robert Ashley met with Wolgamot a few more times over dinner, but eventually they dropped out of contact. Years passed, and in the 90s, Robert Ashley was informed that John Barton Wolgamot had passed away in 1989. And that, to Ashley’s shock, Wolgamot had left him with the rights to his published works. Additionally, Ashley was to receive the plates for his third and final unpublished book. He received only one plate: a title page. Upon it was the name “Beacons of Ancestorship: A Symphonic Study of the Rejuvenation in the Grain.”

John Barton Wolgamot was a lot of things, but I am confident that what he was not was crazy. He had a strong, beautiful vision that I don’t understand, Robert Ashley didn’t understand, and Keith Waldrop didn’t understand; however, there is a palpable internal logic to his work that is undeniable. In his liner notes, Ashley ends with a beautiful final note:

“I do know that for Wolgamot there was a reason, a logic, for the choice of every name, for the grouping of those names and for the choice of every adverb. I believe that the absolute formality of the text touches in us a fact that is as deep as our humanity: the fact is that everything in our speech and in our thinking is elaborately organized, even before we get to it. To have an idea is to have a thought about how to refine that organized material, to make it more beautiful.”

In the creation of his book, John Barton Wolgamot invented (by necessity) an entirely original style, in order to convey his idea of names as the basis for rhythm and, in turn, language. Ashley recalls a meeting with Wolgamot in which he walked through a page, articulating clearly the ways in which names like William Somerset Maugham and Oland Russell conveyed an idyllic island landscape (“Somerset has both summer and set as in sun-set, and Maugham sounds like the name of a South Pacific Island, and Maugham wrote a biography of Gauguin, which name has both ‘go’ and ‘again’ in it, and Oland could be ‘Oh, land,’ a sailor’s cry…”) Yet, Wolgamot was an artist, not a teacher, and had neither the skill nor drive to explain the entirety of his work in common vernacular. In fact, I believe it would have diminished the work to do so; after all, if his goals had been achievable with standard language, why bother inventing a new one?

For this reason, it can be hard to understand experimental works of art as an outsider, and harder still to ensnare others once you’ve broken your way in. Artists who work outside of popular vernacular do so because they find it limiting, and so how could they possibly explain their work in terms which they struggle so desperately against? How could Wolgamot possibly explain the intended effect of a poem/novel/tome which has almost no bearing on past works, save maybe Beethoven’s Eroica? And how can I possibly explain to you the breathless and entrancing sonics of Ashley’s adaptation in language? As Kyle MacLachlan so eloquently phrased it in his deeply moving obituary for David Lynch, “David didn’t fully trust words because they pinned the idea in place. They were a one-way channel that didn’t allow for the receiver. And he was all about the receiver.”

I’ve been hosting my radio show focused on avant-garde sound works (“Beat Generation”) since January 2024. An unintentional but enduring area of focus has been the history and legacy of a certain largely French branch of tape music; originally called “Musique Concrète” by its forefather and main proponent, Pierre Schaffer, it now goes by the more general term “Electroacoustic Music.” Coming to this music as an outsider is daunting; most pieces contain precious few intoned notes or harmonies, let alone traditional instrumentation. It is a music of acoustic events, whether that be the slam of a car door or the crunching of a leaf. Without guidance, this music can seem illegible, impenetrable, or even downright frivolous, but with further context can be seen as a radical — and at times very moving — new art form allowed by the innovation of recorded sound. Composers like Schaffer, Luc Ferrari, Bernard Parmegianni, Dennis Smalley, and countless others spent their lives exploring the bounds and possibilities of this novel medium, and landmark pieces like Ferrari’s “Presque rien,” Parmegianni’s “De natura sonorum,” or Smalley’s “Pentes” give us a window into this boundless new world. In the 1950s and 60s, broadcasts on French national radio by the Groupe de Recherches de Musique Concrète (GRMC) brought this exciting new world of sound to much of continental Europe, inspiring massive bands like The Beatles, Pink Floyd, and Kraftwerk, in addition to more underground acts like Cabaret Voltaire, Swell Maps, and Throbbing Gristle, all artists who younger artists still cite as inspirations on their own work.

It’s still relatively common to see music referred to as a “universal language.” I frankly believe this couldn’t be further from the truth. Music is deeply contextual, from the omnipresent cultural expectations of your birthplace, down to the day, time, place, and mood at which you come into contact with a piece of music. Without a mainstream contemporary equivalent to the GRMC broadcast, I had very little cultural context with which to appreciate electroacoustic music. Fortunately, I was able to check out the sole copy of “The Language of Electroacoustic Music” by Simon Emerson at the UCSB Music Library (I urge students to take advantage of their university access while they still can). This text was invaluable to my understanding of electroacoustic music, and learning the ways in which composers thought about recorded sound and its manipulation vastly deepened my understanding of this music. When I began to immerse myself in the ideas of this work, I began to see new forms peeking through everyday sounds. I began to feel the emotion and intention behind the construction of the work, and began to savor how the tones and textures evolved over time. I started hearing the music not as an assemblage of sound, but as a cohesive composition.

But “The Language of Electroacoustic Music” has been out of print since its initial 1986 run, and the few digital versions are either behind an academic paywall or hosted on sites like the Internet Archive — which seem less and less permanent in recent years (see here). In fact, the liner notes for “In Sara, Mencken, Christ and Beethoven There Were Men and Women” are only digitally available on Ubu Web — an incredible digital library for avant-garde film, sound, and literature — which shut down new archiving in 2024, and during research for this article went down multiple times. It always managed to come back up, but every time could have been its last, and countless one-of-a-kind stories like this would have gone with it.

But there is some light to be had. As of February 1st, 2025, Ubu Web decided that due to the ongoing political upheaval in the US and around the globe, they would resume their archival work, posting a statement that included the following:

“In a moment when our collective memory is being systematically eradicated, archiving reemerges as a strong form of resistance, a way of preserving crucial, subversive, and marginalized forms of expression. We encourage you to do the same. All rivers lead to the same ocean: find your form of resistance, no matter how small, and go hard. It’s now or never. Together we can prevent the annihilation of the memory of the world.”

I, like Ashley, believe that these “outsider” works of art allude to something more fundamental in the way we experience our world. Emerson’s book did more than teach me about an obscure form of modern art music, it broadened my scope of what music could be. It made my world larger and more free. Similarly, reading Ashley and Waldrop’s accounts of Wolgamot as a man and an artist instilled me with an unshakable sense of mystery and possibility in the everyday. It is essential work to preserve historical art, yes, but it is just as important to record the aims of the artists, the context they created from, and the methods and avenues through which this art reached the contemporary public. Otherwise, it’s all just noise.

Great art allows us to speak, through time and space, to people unbelievably different from ourselves, to cross that great void and reach out a hand. No matter how fanciful we might find his story, Beethoven’s Eroica spoke to John Barton Wolgamot one day in Central Park. Keith Waldrop recalls Wolgamot’s stated intention for his book, said in a letter he received in 1980: “Near the very end, at the bottom of the Corot page, you could hear Beethoven speak. Loud and clear and in English.” I have neither the context nor the intellect to understand Wolgamot’s vision, and it breaks my heart that I cannot hear Beethoven like he could. I’m sure it would be breathtaking.

P.S. If you take nothing else from this story, let it be the fantastic resources with which you can find world-broadening, entirely individual works of art. In a time where art and entertainment are becoming indistinguishably enmeshed, I urge you to visit ubuweb.com and click literally any random link — it will likely open up new worlds for you. Take advantage of the public library system, especially if you have access to an interlibrary loan program! Experimental music journalism is still alive and well on Substack, and I highly recommend Tone Glow, a closer listen, Futurism Restated, and zensounds, among others. Also, The Wire is still publishing great stuff on essential underground work, as they have been since 1982. And, of course, there’s always radio, whether on the air or online at places like NTS, Dublab, and countless others. Even Wikipedia has some great resources to get you started. Above all, don’t be afraid to talk to people involved in the art you love, from record store employees to professors. These stories are still alive and out there, and, as trite as it may seem, the work of carrying them into the future really is up to us. Get out there and explore. -LH